Accumu Vol.25

集団人間行動と陶器

京都情報大学院大学 講師

Andrew Vargo

I have always been interested in the economics and structures of group behavior. My current research focuses on how online communities aggregate knowledge and gate-keep their social systems. It can be nearly impossible to explain and predict how a community of practice is conducted. What we expect to be true is often false, and the readiest explanation for a phenomenon can be misleading.

During the summer of 2003, I was fortunate enough to go on a university group trip to Japan. At this point, I had no long-term plan to be in Japan. This month-long class was based in Kyoto, but had the oddity of having the first three days in Matsuyama, Ehime. In a jet-lagged haze, our small group of twelve students was treated to a barrage of new and esoteric experiences. With little context, we saw multiple sites of Kūkai’s temples in the Shikoku Pilgrimage (四国遍路), visited Matsuyama Castle, and saw cemeteries from the Russo-Japanese war. The lack of context is not criticism of the class leader. It is difficult to convey meaning or significance to beings who are quite nearly blank slates. In my case, every new experience was almost overwhelming.

On the third day of the trip, we all got on a tour bus and headed to a small town of about 20,000 inhabitants adjacent to Matsuyama called Tobe-cho (砥部町). We were told that we would be seeing a Japanese pottery, called Tobe-yaki (砥部焼). It was here that my life completely changed.

Entering Tobe-cho via the highway, it was impossible not to be struck by the incredible number of places, stores, kilns, and houses, exhibiting Tobe-yaki. I had never seen a town so dedicated to one subject as this. There were pieces of pottery in all directions and I distinctly remember thinking that every resident must have kitchens overflowing with a plethora of bluish-white vessels in their homes, apartments, and offices.

It is important to again remember that I had almost no context for what I was seeing. Rural Japanese towns and cities are extreme in their dedication to a local art, craft, or food. For example, if one goes to Aomori, you will be immediately struck by how many amazing prints and images by the great Munakata Shiko decorate the city; it is more than an image at the train station or a nice museum, it is the repetition of works available around every corner that is so striking. Visiting Uji city will leave many visitors convinced that the town’s economy is based mostly around green tea. To an uninitiated outsider, this type of dedication can seem excessive. Certainly, North American towns have themes and are proud of their local heritage and heroes, but not to the level or manner exhibited in Japan.

Being that this was my first experience, I thought that Tobe-yaki must be one of the most important ceramics in all of Japan. I was utterly convinced. Why else would they build so many places dedicated to it?

The pottery itself was somewhat hard to understand. The bluish-white of the pieces and brutishness of the vessels were handsome, but not what would be stereotypically “Japanese” in my opinion. Shigaraki-ware or Bizen-ware , with their dark and complex colors fit better into what a foreigner would expect. Tobe-yaki is, instead, almost clinical in its appearance; beautiful but utilitarian.

This makes sense given the history of the ceramic style. Tobe-yaki was started in the 18th century as a commercial good for the Ozu Clan and was exported to Qing China in the 19th century. While there were numerous artistic developments in the ceramic style, there was an emphasis on it being a utilitarian commercial craft. This does not discount the style, but this does not share the same romantic history as ancient ceramics styles dedicated to tea ceremony.

私はいつもグループ行動の経済と構造に興味を抱いてきました。私の現在の研究は,オンラインコミュニティが如何に知識を集約し,社会システムを維持しているかに焦点を当てています。コミュニティの実践が如何なるものであるか説明し予測することは,ほとんど不可能とも言えます。これが正解であろうと予想していることが,間違いだということはよくあり,またある現象を分かりやすく説明した記述が誤謬を孕んでいることも頻繁にあります。

2003年の夏,ありがたいことに大学を通じて日本への旅行プログラムに参加にすることができました。当時はこんなに長く日本に滞在することになるとは思っていませんでした。私の参加した研修旅行は一カ月間の京都を拠点にしたプログラムでしたが,不思議なことに最初の3日間だけ,愛媛県松山市にて滞在するものでした。時差ぼけの霧の中,参加した我々12人の学生は,新しく神秘的な経験をもって日本の滞在の幕を開けることとなりました。そこで何の脈絡もないままに,四国遍路の空海にゆかりある寺院をいくつか訪れたかと思えば,松山城を訪れ,日露戦争の墓地を見ました。文脈を欠いていたことについて,私はこの旅の班長を批判するつもりはありません。私はすべての経験にただただ圧倒されるばかりでした。何もかもが目新しい参加者に対しそれぞれの意義や意味を伝えることはおおよそ困難でしょうから。

旅行の3日目には,ツアーバスに乗って,松山に隣接する人口約2万人の小さな町,砥部町に向かいました。そこで砥部焼と呼ばれる日本の陶器を見ることができるだろうということでした。そしてまさにこの場所で私の人生を完全に変える経験をしました。

高速道路を通って砥部町に入ると,砥部焼を展示している数多くの場所,店舗,窯,家に目を奪われました。こんなにも一つの主題に専念した町を見るのは初めてでした。どこを見ても陶器があるので,きっと住民の家やオフィスは皆,青と白の器で溢れかえっているに違いないと想像したのを記憶しています。

繰り返しになりますが,当時私は自分が見物している対象について何の文脈も持たなかったのです。日本では田舎に行くと地元の芸術品,工芸品,食べ物が数多く展示されています。たとえば,青森に行けば,棟方志功の版画が町の至る所に飾られているのを目にするでしょう。駅舎や美術館で目にするイメージとは異なり,街角のあらゆるところで芸術に繰り返し出くわすことができます。宇治市を訪れれば,この街が緑茶を中心にした経済で成り立っているものだと多くの訪問者は確信するでしょう。外部から訪れる新参者にしてみれば,一つの対象にここまで打ち込んで公開する様子は過度に見えるかもしれません。北米の町も,特定のテーマを持ち,地元の遺産や英雄を誇りに思う習慣がありますが,日本での見せ方やその度合いと比べれば全く別次元のものです。

これが私の最初の経験だったので,私は,砥部焼は日本中で最も重要な陶器の一つに違いないと思いました。私は完全に確信していたのです。何せこんなにも陶器に専念した町はきっと他にはないはずだから,と。

砥部焼の陶器そのものは幾分か理解しづらいものでした。青と白でできた器は荒々しくハンサムな印象ですが,私の考えるステレオタイプ化された「日本ぽさ」は感じられないものでした。信楽焼や備前焼に見るような,濃い色や複雑な景色のある陶器は外国人の期待に副います。それに比べ砥部焼は,美しいけれど随分と飾り気がなく実用的です。

これは陶芸史を考えると理にかなったものです。砥部焼は,18世紀に大洲藩の商業として始まり,19世紀に清に輸出されました。陶器の手法には数多くの芸術的な変化がありましたが,実用的な工芸品であることに重点が置かれていました。実用性は美しさを損なわないものの,砥部焼には,茶道に捧げられた中世の陶器の持つようなロマン主義的な歴史を持ち合わせていません。

We spent around five hours in the town, visiting the museum and a local kiln. At the kiln group members were tasked with decorating their own wares, a very plain cup and plate set, with designs before firing. In all honesty, I was not particularly enthused to be doing this. For one, I was embarrassed by the designs of my compatriots, which were invariably some gauche imagination based on a children’s anime. My mind was blank as to what design I should paint on my wares. Looking at the delicate designs in the studio, everything I thought of felt horribly unoriginal or culturally insensitive. Is it inappropriate for an American student to represent the 日の丸 on a piece of ceramic? It seemed to me that it was. Eventually, I settled on a Macedonian Sun, using red and yellow. It was crude, but I felt it had some sort of weight. Certainly, better than something from Dragonball.

Of course, a classmate then asked me what anime it was from. Such is life for the pretentious.

The studio master was a young man who was cheerful and clearly happy about our presence. Towards the end of our stay, we learned about his history and about Tobe-yaki in general. He said that there were dozens of kilns in the area with hundreds of potters and I was even more convinced that this pottery must be incredibly popular in Japan!

A few days later, I arrived in Kyoto to start studying Japanese and visit various locations for my class. I was doing a home-stay in Fushimi-ku, in a mid-century house with a beautiful and historically significant garden. The host-family was not only wonderfully kind, but hey also had their home appointed with wide-range of ceramics. Out the various styles, none even closely resembled Tobe-yaki. I asked them about their collection and what it was lacking, and they claimed they had never heard of the style.

This was certainly an anomaly. How could it possibly be true that a family, well educated and interested in Japanese art, could not know about Tobe-yaki? But, as I began to ask more and more people, such as my teachers at school, it began to dawn on me that the pottery was not well known. That is really when I began to realize that I did not even begin to understand what I had seen and experienced in Tobe-cho.

At the end of our trip, the items that we had decorated where sent up to Kyoto and given to us. Everyone unwrapped their plain cups and dishes with their designs, but I received something different. My pieces had broken in the kiln (thankfully), so the studio decided to give me a very pretty wall-vase with a delicate flower design.

I was thrilled. Now, I had an actual physical representation of Tobe-yaki that I could show my family and friends, and instead of having my embarrassing designs it had something that invoked what I had seen in the town. And now I was also completely confused. What was Tobe-yaki and why was it so heavily represented in the town? Was it the result of the sunk-cost fallacy, where the promise of Mingei stardom had fooled the town into supporting an unknown art? Or was there a bigger industry that was supporting a show of local pride?

a picture of the sun design that I tried to make. 太陽をモチーフに私が器に描いた絵

私たちは町で約5時間を過ごし,博物館と地元の窯を訪れました。窯では素焼きの湯呑と皿の絵付け体験に参加しました。正直に言うと私にとってそこまで夢中になる作業ではありませんでした。というのも参加した仲間がみな,子ども向けアニメを元にしたぎこちない発想の図案ばかりで気恥ずかしかったのです。自分の器にどのような絵を描くべきか,私は頭が真っ白な状態でした。工房にある繊細な図案を目にすると自分の思いつくものはどれも独自性に欠けるか,デリカシーのないもののように感じました。日の丸を描こうと思いましたが,アメリカからやって来た学生が陶器に日の丸を描くのはどうも不適切に思えました。最終的に,私は赤と黄色を使ってマケドニアの太陽を描くことに落ち着きました。粗末な絵でしたが,ドラゴンボールの絵を描くよりは,ある種の重みがあるような気がしたのです。

そうは言っても,すぐにクラスメートからこれは何のアニメを元にした絵なの?と聞かれました。見た目ばかりを気にする同輩にとって,私の描いた絵なんて結局そんなものなのでしょう。

工房の主人は,明るい男性で私たちの来訪を喜んでいる様子でした。滞在の終盤にかけて,砥部焼の概要と彼の経緯について教えてくれました。あたりには数十の窯があり何百人もの陶芸家が暮らしていると聞き,私は砥部焼が全国的に大流行しているに違いない!という確信をさらに強めました。

数日後,私は京都に到着し研修が始まると,日本語学習とオリエンテーションで様々な場所を訪れました。ホームステイ先は伏見区にある美しい庭のあるレトロな家でした。ホストファミリーはとても親切で,なんと家中には多岐に渡る陶器が置かれていました。ところがその中には,砥部焼らしいものは一つもありませんでした。不思議に思って私は,見事なコレクションですが砥部焼を忘れていませんかと尋ねました。するとそんなものは聞いたことがないとの返事が返ってきました。

おかしい…教養のある日本芸術に関心を持つ家族が,砥部焼について知らないわけがないはず…私は不思議に思いました。しかし,日本語の先生をはじめ,多くの人々に尋ねていくと,この陶器があまりよく知られていないようだということがだんだんと明らかになってきました。こうして私は砥部町で目にし,経験したことに対して,何か思い違いをしているらしいということに,ようやく気付き始めたわけです。

旅行の終わり頃,私たちが絵付けした皿が焼き上がり京都に届きました。みな包装を開け,各々のデザインの湯呑と皿を手にしましたが,私だけは違うものを受け取りました。幸か不幸か,私の作品は窯で割れてしまい,代わりに工房は繊細な花の絵が施されたとても美しい一輪挿しを送ってくれたのです。

家族や友人に見せびらかすことができる本物の砥部焼を手にしたことに胸が躍りました。自分の粗末な図案よりよっぽどましなうえ,町で見たものを想起させる思い出の品を手に入れることができました。ところが同時にわたしの頭の中は混乱していました。砥部焼とは何だったか,あんなにも町中で誇示されていたのは何故だったのか…。誰も知らない民芸品をスターダムにのし上げようと町中がその気になって,コンコルド効果から抜け出せなかったのではないか?それとも,地元のプライドを示そうとした何らかの大きな業界の後ろ盾があったのではないか?

Upon arriving home, I set about researching everything about Tobe-yaki. The World Wide Web was still young, but I could access enough materials and translate enough Japanese to gather all sorts of information. I learned about the Mingei (民芸) art movement, Yanagi Sōetsu, Hamada Shōji, and Bernard Leach, and I slowly pieced together a speculative version of why Tobe-yaki existed as it did. I wanted to find out more, and so, after convincing a school friend, applied for and received a research grant to study Tobe-yaki. Our primary interest was in researching and documenting the socio-economic significance of the ceramic on the local population and economy.

Receiving the research grant allowed us to visit Shikoku and study the town on-site. It was a very challenging experience. After a few weeks of note-taking, photographing, and interviewing residents, I started to realize that I was getting no closer to understanding why Tobe-yaki existed the way it did. There did not seem to be a strong financial incentive for the dedication and it was clear that while the town was hungry for tourists and visitors, relatively few stopped by. But I did keep hearing how important the ceramics were to the residents. Simply, the residents of Tobe-cho were happily devoted to Tobe-yaki.

I think that this is an important thing to remember when studying group behavior. The quest to neatly explain everything based on pure financial reasoning or typical cost-benefit analysis is foolhardy. Indeed, when we consider how humans volunteer their time to create online encyclopedias of knowledge, the idea that they do so for free is surprising (we also know that when they are paid, they do not do as good as a job as when they volunteer their efforts for free).

After our on-site research, we went to Aoyama Gakuin University for what was supposed to be four months. I started studying economics and Russian Studies. I found that Aogaku was an incredible and supportive atmosphere, one that encouraged me to do more research and to study interesting things. It was here that I began to become interested computer-human interaction and online communities.

I am grateful that I found Tobe-yaki. It helped introduce me to Japanese culture and to the field that I love working in. And, it started one of my favorite hobbies: going to a small town in Japan and discovering the local specialty.

帰国すると,私は砥部焼のすべてを調べあげようと,ワールドワイドウェブの情報を貪りました。WWWは未だ青年期でしたが,十分な資料にアクセスでき,収集した情報を日本語に翻訳するには十分でした。調べていくうちに私は民芸運動,柳宗悦,濱田庄司,バーナード・リーチについて学びました。私はだんだんと砥部焼がなぜあのような形で存在したのか,憶測をまとめていきました。なんとか学校の友人を説き伏せて,砥部焼を研究するための研究助成金を申請しました。私たちの主な関心事は,地元住民と経済における陶芸の社会経済的意義を研究し,文書化することでした。

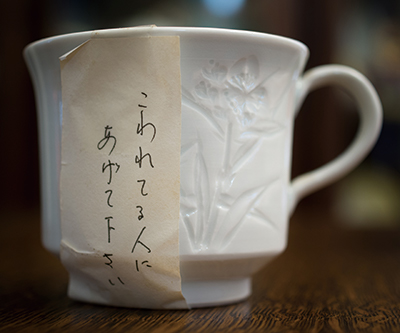

a cup indicating the package that was for the person (me) with the broken vessels. 窯で器が割れてしまった参加者用に用意されたカップ

研究助成金を得て,私たちは四国を訪れ,現地にて調査を開始することができました。それは非常に挑戦的な経験でした。数週間に及ぶノート取りと,撮影,インタビューを経たのち,私はちっとも砥部焼についての理解が深まらないことに気づきました。金銭的インセンティブはまるで見当たらず,町は観光客に飢えているものの実質的に観光に来る人が稀であったことは明らかでした。それでも私は陶器が住民にとってどれほど重要であるか聞いていました。つまり,砥部町の住民は砥部焼が好きで喜んで身を捧げていたわけです。

こうしたことは集団の行動について研究するときに覚えておくべき重要なことだと思います。金銭的な動機やよくある費用対効果の分析をもって何もかもきれいに説明しようとすることはあまりに向こう見ずです。いかにも,人間が知識をもとにオンラインの百科事典を創ろうと自らの時間を費やしたことを鑑みれば,そうした行為が無償であったことは驚くべきことです。(もっと言うと,有償になると無償でのボランティアに比べ出来栄えが劣ることもわかっています。)

現地調査の後,青山学院大学に通いました(当初は4カ月だけの予定でした)。そこで私は経済学とロシア研究を始めました。青学は非常に協力的な雰囲気で,さらに研究をし,興味のあることを探求するよう勧めてくれました。こうして私はコンピュータと人間の交流とオンラインコミュニティについて関心を持つようになり今に至るわけです。

私は砥部焼との出会いに大変感謝しています。砥部焼は私を日本の文化や仕事が大好きな分野へと導いてくれました。そして,私に新たな趣味を始めるきっかけをつくってくれました。暇があれば日本の小さな町に行きその特産品を堪能することは,私にとって何よりの楽しみになりました。